By Sister Mary Acerbi

What is the meaning of the story of Jesus’ encounter with the money lenders? All four Gospel writers relate the story of the Cleansing of the Temple, but Matthew is the only one who proclaims, “the blind and the lame approached him in the Temple area and He cured them.” (Mt. 21:14)

What is the meaning of the story of Jesus’ encounter with the money lenders? All four Gospel writers relate the story of the Cleansing of the Temple, but Matthew is the only one who proclaims, “the blind and the lame approached him in the Temple area and He cured them.” (Mt. 21:14)

Theologically speaking, we are all temples of the Holy Spirit, the Mystical Body of Christ. When any one of us abuses the Temple, we abuse the whole body of the Spirit, and thus we become like the money lenders. We are abusing the Body of Christ.

I last saw the window as I walked down the left side of St. Joseph Chapel in late December, up to the Sanctuary leading into the Adoration Chapel. I couldn’t help but think of St. Theresa of Calcutta’s response to a reporter who asked her, “What’s wrong with the Church today?” She responded, “You and I, sir, are what’s wrong with the Church.” She must have had in mind the fact that we are the Church, the Temple not made with hands.

We are all the Temple, and yet we abuse it in so many ways. I work in a school that serves poor children, most of them Black and Hispanic. It is abuse of the Temple when children come to school hungry or without proper clothing, especially in extremely cold weather, because our greed has deprived them of what they need.

According to 2 Samuel 5:8, “the blind and the lame” were forbidden to enter the Temple, but Jesus said no, cleansing is what’s needed. The school where I work is a family school, where we provide our children with what is needed for both body and soul. Thanks mostly to donations, we are able to meet the educational needs of our children. How can we, like Jesus, cleanse the Temple?

Branches of the Lord

A poem by Sister Mary Acerbi

How can we turn our hearts from the faces of the children? These branches touching miracles, saying, You are my hands, you are my smiles, you are my tears, you are my laughter, you are my clumsy feet. Who will feed my hunger? Who will bear my pain of not knowing the dreams passed on as faith? Who will feed the love in my heart?”

Tell me: “Is it You, is it I, and when will we see the angels protecting her branches that reach the hearts of us as gift?”

Gift from a loving God, filling the gap in the future.

Gift that unites a friendship born in the faces of the children. Gift as a blessing!

Tell me, “Is it You, is it I and when will you and I be WE?

When you and I become the WE in the Church, the WE as the Temple, cleansing the WE in the Body of Christ, only then WE will cleanse the Temple.

By Sister Joan Kaepplinger

In the Sermon on the Mount window, all people from the east and the west learn from Jesus the Teacher that we are created in God’s image. In Jesus, God came in flesh to be like us. Jesus came telling us that he is the way, the truth, and the life. He is the light of the world. He taught us from the mountain.

In the Sermon on the Mount window, all people from the east and the west learn from Jesus the Teacher that we are created in God’s image. In Jesus, God came in flesh to be like us. Jesus came telling us that he is the way, the truth, and the life. He is the light of the world. He taught us from the mountain.

(As an aside, I first must share the story of the name given to me on my Reception Day as a School Sister of St. Francis, June 13th, 1947. I was given the name Sister de Alverno, which was one of the three names that I hadn't asked for! Yet I was deeply moved by the significance of the mountain that was so special to St. Francis. What profound feelings overwhelmed me! I had entered the convent from Alvernia High School in Chicago, where I was inspired by the creative new energy of the best teachers in the world, especially my freshman homeroom teacher, my art teacher, and my sociology teacher - all School Sisters of St. Francis so involved in what was happening in the world. Their exuberance caught fire in our hearts and I wanted to be part of that.)

Now, as I reflect on the Sermon on the Mount, I identify with the Teacher and students in this window. Jesus, radiant and with arms outstretched, is blessing his students. They look into the eyes of Jesus and listen intently, not missing a single word.

In Chapter 5 of St. Matthew’s Gospel, we read how Jesus went up on the mountain and taught the Beatitudes: Blessed are the poor in spirit, those who mourn, the meek, those who hunger for justice, the merciful, the pure of heart and the makers of peace. Jesus also said those who are persecuted for acting rightly would be blessed, as are those who are reviled for following him. Be glad and joyful, he said, for your reward in heaven is great.

How blessed are we School Sisters of St. Francis and associates! We have been called to never stop listening to the needs of the times. We are each a unique listener in a community of listeners. We also believe that we are all teachers of the Beatitudes.

May this beautiful window touch the hearts of all who walk through St. Joseph Chapel and see it, as well as of those people around the world who see this image on our website.

By Sister Carol Jean Ory

Where do we go to look for the Tree of Life? The Quran calls it the Tree of Immortality. The Christian Bible tells us that it is not the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. It is a tree still standing in the Garden of Eden, guarded by cherubim with a flaming sword (Genesis 3:24).

Where do we go to look for the Tree of Life? The Quran calls it the Tree of Immortality. The Christian Bible tells us that it is not the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. It is a tree still standing in the Garden of Eden, guarded by cherubim with a flaming sword (Genesis 3:24).

But St. Gregory the Great tells us that the fruit of the Tree of Life is Jesus in the Eucharist. That flaming IHS ensconced in the uppermost branches of the Tree of Life in the St. Joseph Chapel balcony window is a beautiful tribute to the teaching that Eternal Life is among us, not still imprisoned in Eden.

In our window, “Glory to God” is scrolled across the top of the Tree of Life. Where does the glory of the eternal love of God shine more brilliantly and more lovingly on humankind than in the Eucharist, and on those who daily live out its meaning?

St. Joseph Chapel is a concrete expression of our community’s devotion to the Eucharist, to the Body of Christ given up for us as food and nourishment. The School Sisters of St. Francis carry on that devotion to the Body of Christ, a Body that lives and dances and suffers in each human being, and in all of Creation.

Not long ago, in Juarez, Mexico, one of our sisters serving at Casa Alexia, our mission on the U.S.-Mexico border, saw a drug-addicted man violently trying to shake a good-sized tree close to a parishioner’s house. Did that tree somehow symbolize the addict’s life? Was it, to him, the image of a fatherless home; a demanding, factory-working mother; the lack of funds for an education; a quick-feel-better-deal of trafficking in drugs, and the anguish and anxiety of not always being able to get them?

Tree of Life, Body of Christ, save us. Give life in abundance to us and for all of us.

By Dr. Eleanor Fleming, Associate

When one sees a peacock, one is often in owe of the peacock’s beauty, its brilliant feathers, and the way it struts around. The peacock is often a symbol of pride, confidence, and vanity. But the peacock has other meanings in the context of theology and Biblical text.

When one sees a peacock, one is often in owe of the peacock’s beauty, its brilliant feathers, and the way it struts around. The peacock is often a symbol of pride, confidence, and vanity. But the peacock has other meanings in the context of theology and Biblical text.

The peacock appears in early Christian art symbolizing immortality and Christ’s resurrection. Legend had it that the flesh of the peacock did not decay. St. Augustine in The City of God writes about keeping a piece of peacock flesh long enough for it to decay, yet the peacock flesh did not become foul. After a year, the peacock flesh was still in the same condition, only smaller and drier. And when a peacock molts, its feathers come back fuller and even more brilliant than before. For these reasons, the peacock was thought to be immortal.

In the Bible, the symbolic meaning of the peacock is less clear. The peacock occurs in the Bible once: “The king had a fleet of Tarshish ships at sea with Hiram’s fleet. Once every three years the fleet of Tarshish ships would come with a cargo of gold, silver, ivory, apes, and peacocks” (1 Kings 10:22). Here, the reader learns of Solomon and his immense wealth, and that he had the ability to bring in ships filled with exotic animals. In this way, the peacock is associated with wealth.

What is interesting in the peacock’s connection to Solomon is not his wealth, but his wisdom. Solomon asked that God give him a “listening heart” (1 Kings 3:9). God gave Solomon discernment to know what is right and “a heart so wise and discerning that there has never been anyone like you until now, nor after you will there be anyone to equal you" (1 Kings 3:10-11).

While I do not know the history of the peacock window in the reliquary chapel, I imagine that the window is meant to serve as a reminder to the School Sisters of St. Francis that in the ministry of the sisters and associates, we are called both to be living witnesses to our belief in the resurrection and to serve with listening hearts. When we act from a place of wisdom that is centered in Christ, we can love more, serve more effectively, welcome the lost, heal the broken, and do our individual parts, however we are called, to make this world our heaven on earth.

In a world that often uncertain, we may be quick to react to the chaos around us, become filled with doubt or fear, or to strut around like the peacock filled with our own vanity. But if we use our listening hearts and turn to God in prayer, we will know and have peace. We can then discern what is true and what is illusion. Let us be the peacocks in our communities, using our work to spread the message of hope in the resurrection to all.

By Sister Ramona Ann Schmidtknecht

Long before the official recognition of the Blessed Virgin Mary’s Assumption into Heaven and recognition of the Queenship of Mary, Mothers Alexia and Alfons linked devotion to Mary with devotion to St. Joseph.

Long before the official recognition of the Blessed Virgin Mary’s Assumption into Heaven and recognition of the Queenship of Mary, Mothers Alexia and Alfons linked devotion to Mary with devotion to St. Joseph.

This window depicting Mary being crowned Queen of Heaven and Earth is prominently placed high in the north transept. The Blessed Trinity is as visible as Mary. To Mary’s right, we see the Father, King and Ruler; to her left the Son, King and Victor, ready to crown His Mother; above, the Holy Spirit is giving gracious approval.

Angels surround Mary and below her cold be saints who died before Mary, or Apostles present at her death. Is it possible that St. Joseph is among them (with staff in hand)? Do we not feel joy and hope when we see a rainbow, just as Noah did? Check carefully behind Mary!

Mary has long been honored as Queen in devotional prayers, religious art, and songs. Early writers of the Church often referred to Mary as Queen, a logical conclusion since her Son is King. How often have we sung Salve Regina or prayed “Hail, Holy Queen”? We honor Mary as Queen in the Rosary, the Franciscan crown, and each May as we crown Mary. In her Litany, we honor Mary as Queen no less than 13 times and Mother 11 times.

The early Christians believed that Mary was assumed into heaven and by the sixth century the feast of the Assumption was celebrated in the Eastern Church. Only more recently did the Roman Catholic Church give its official recognition to her Queenship:

- 1950: Pope Pius XII declared the Assumption a dogma of the Church

- 1954: Queenship of Mary celebrated on May 31

- 1964: In Lumen Gentium, the Second Vatican Council states “Mary was taken up body and soul into heavenly glory and exalted by the Lord as Queen of the Universe.”

- 1969: Pope St. Paul VI moved Queenship to August 22, octave of Assumption

- 1995: Pope St. John Paul II added the title “Queen of Families” to the Litany

- 2018: Pope Francis established Mary, Mother of the Church celebrated the Monday after Pentecost

Personally, Mary has been part of my daily life. Each night we knelt around the kitchen table and prayed the Rosary and the Litany of Mary. I was in eighth grade when the dogma of the Assumption was proclaimed, and we prayed the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary each day when I entered the convent. Our class in 1954, a Marian Year, chose Mary, Queen of the Seraphic Order as our patron.

In her poem, “Litany for Ordinary Time,” Sister Irene Zimmerman focuses on Mary, our Queen, in everyday life. In this Litany we see Mary “queen of spinning wheel,…of scrubbed floors,…of skinned knees, …of fresh-baked bread,…of ordinary time and space.”

Where do we find Mary as Queen? Today, for example, would we add the title Queen of Immigrants?

Mary, you are Queen of Heaven and the Universe, but you are also Queen of virtues to imitate, of daily tasks we must complete, of ways to serve your Son.

By Sister Anna Wolfe

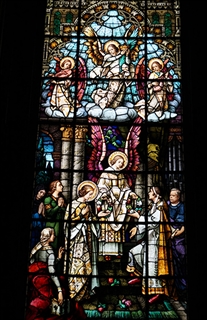

Of the many possible depictions of St. Jerome, the foundresses of the School Sisters of St. Francis chose as the inspiration for our St. Joseph Chapel window an altarpiece titled “The Last Communion of St. Jerome.” It was painted nearly 1,200 years after the saint’s death by Domenico Zampieri, who was commissioned to do the piece by a group of cardinals as a decoration for a room in their villa in Rome about 1614.

Of the many possible depictions of St. Jerome, the foundresses of the School Sisters of St. Francis chose as the inspiration for our St. Joseph Chapel window an altarpiece titled “The Last Communion of St. Jerome.” It was painted nearly 1,200 years after the saint’s death by Domenico Zampieri, who was commissioned to do the piece by a group of cardinals as a decoration for a room in their villa in Rome about 1614.

Zampieri was a leading practitioner of Baroque Classicism in Rome. The signature features of Domenico’s style, such as the tightly knit grouping of the personages, the accurate facial expressions and sensitive coloring brought the painting fame that, for a time, regarded Domenico’s work as second only to those of Raphael.

Stained-glass artistry is designed to allow visitors to capture a spiritual disposition of the mind-body-spirit connection and fulfill its purpose of enhancing the worship space. We can ponder on our sense of oneness with the replication of our own reflections within the painting. Jerome believed that “Anytime we hear the word of God, the Body and Blood of Christ is being poured into our ears. The Divine Word is exceedingly rich, containing within itself every delight.”

Jerome the Scholar

Jerome was born around 342 A.D. and given the name Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus. Let us use the name St. Jerome whose place of birth was in a town which today might be in Croatia or Slovenia. His parents were assumed to be wealthy Christians. As a youth Jerome traveled to Rome to pursue his first passion – learning.

Jerome’s parents made great efforts to instill proper manners and behavior, but Jerome followed worldly pleasures. Fortunately, Jerome’s passion for learning and constant search for truth led him through the journey to sanctity. Jerome was greatly influenced by a friend and companion, Bonasus, who was a Christian. He became interested in theological matters, faith and the life-style of his friend. His conversion to Christianity occurred about age of 25.

Jerome the Monk

The Christian life-style of Bonasus drew Jerome into friendships with other Christians, noted clergy and teachers. Pope Liberias baptized Jerome; Bishop Saint Valerius was the abbot who was Jerome’s superior when he entered the monastic life. It was Pope Damasus who persuaded Jerome to be ordained. After Jerome’s strong temper and criticism made him unpopular, Pope Damasus granted him freedom to travel and study extensively.

When Jerome retreated to the wilderness with his library, he learned Hebrew and undertook his most famous contribution to the Church and humanity: the translation of the entire Bible into Latin, the common language of the time. The Vulgate Bible of St. Jerome was the official text of the Church for more than 1,500 years. In addition to his studies and writings, Jerome embarked for the Holy Land where he established a monastery in Bethlehem and offering hospitality for pilgrims. He spent his final days living in a cave in Bethlehem, contemplating the scriptures.

Jerome the Truth-Seeker

Jerome’s life on earth was consumed by his search for truth. Would he agree with me that the stained-glass window reveals the complexity of his life? Or that the colors, shapes, mosaics and design capture the mystery of his many human experiences, as we see within our own lives?

Jerome also studied prophecy and the signs of his time. In our own day and age, we are in the midst of mysterious changes and events as well. We School Sisters of St. Francis may have inadvertently, but appropriately followed Jerome’s love for learning. Among this congregation are academic doctors, lawyers, nurses, teachers, culinary experts, pastoral ministers and prophets serving internationally.

St. Jerome’s Feast Day is September 30. St. Jerome, thank you. Pray for us!

By Sister Julia Rice

Wouldn’t it be great to have a portrait to leave behind that tells the best parts of your life story? What if they left out the one thing that was most important to you? That’s what I wondered when I studied the stained-glass window of St. Alphonsus Liguori in the adoration chapel of St. Joseph Convent.

Wouldn’t it be great to have a portrait to leave behind that tells the best parts of your life story? What if they left out the one thing that was most important to you? That’s what I wondered when I studied the stained-glass window of St. Alphonsus Liguori in the adoration chapel of St. Joseph Convent.

First, let’s see what is there. We see a handsome bishop in a glorious red robe kneeling before the Eucharist, above which is an image of Mary. An angel to one side holds a book. Alphonsus was a spiritual writer, lawyer, musician and composer, poet, scholastic philosopher and moral theologian. I think the book is moral theology, but the saint had many books in his life. He wrote 111 works on spirituality and theology. He is a doctor of the Church, one of the great ones.

Not every saint could be pictured in the chapel windows. Alphonsus is there, not only as a saint who had a great devotion to the Eucharist, but because one of the founders of the School Sisters of St. Francis was named Mother Alfons. She actually chose the name to honor one of her spiritual guides, Pater Alfons, a Capuchin, whom she asked to tell her and the other two founders what was the will of God for them. It was his words, “Go to America,” that moved the new community.

But one aspect of the life of the saint that is a connection to our mission today is not in the window. What is missing from the picture? When I looked at it right after reading an encyclopedia life of the saint, I asked, “Where are the poor and marginalized?” You see, St. Alphonsus founded the Redemptorist Order specifically to preach to and to teach the people of the slums in the Kingdom of Naples. That was the need of his time that was not being met. So when Mother Alfonse saw the will of God in the needs of the time, she followed her saint.

That is why I say the window leaves out one of the driving forces of the life of the saint. If you could leave behind your portrait, what would you put in the window of your life? What is that most important thing that might be left out?

By Jim and Mary Ellen Meyer

St. Alexius was born into wealth in the fifth century, the only son of Euphemianus, a prominent Christian Roman of the senator class, and his wife, Aglae. From the charitable example of his parents, Alexius developed a compassionate attitude at an early age. He left his wealthy life, somewhat like St. Francis, to live a life of prayer and extreme poverty. He moved to Syria and lived there for 17 years, caring for the sick and dying.

St. Alexius was born into wealth in the fifth century, the only son of Euphemianus, a prominent Christian Roman of the senator class, and his wife, Aglae. From the charitable example of his parents, Alexius developed a compassionate attitude at an early age. He left his wealthy life, somewhat like St. Francis, to live a life of prayer and extreme poverty. He moved to Syria and lived there for 17 years, caring for the sick and dying.

Eventually, he began to attract attention for his holiness and charity. Not wishing public esteem, he returned to his parents’ home. He looked like a beggar, and they did not recognize him! Being good Christians, they took him in, and gave him a small room under a staircase. He lived in humility, prayer and service to others for another 17 years. It was only upon his death that they recognized Alexius as their son.

True to her namesake, Mother Alexia’s life was one of care for all in need. Already as a young religious (Sister Alexia then) she, with other sisters, operated an orphanage for small children in Schwarzach, Germany. There were never enough resources, and often not enough food. During a typhoid epidemic, the sisters went through the streets, tending to the sick and dying. She was affected by the disease, too, which led to poor health the rest of her life. Mother Alexia’s illness helped her to develop compassion for the sick, orphans and everyone in need.

Choosing a life of Franciscan simplicity and poverty, Sister Alexia left Germany to come to America and respond to needs wherever she felt called. With no funds but much faith, she began her first convent in New Cassel (now Campbellsport), Wisconsin. Other women were soon called to follow her inspiration and holiness. Later, Mother Alexia’s experience with hydrotherapy treatments in Germany inspired her to establish Sacred Heart Sanitarium to bring these new water therapy treatments to Milwaukee.

The St. Alexius window is one of 115 in St. Joseph Chapel. Sadly, Mother Alexia never saw it, for she was in declining health and living in Germany before the chapel’s construction began. By the time it was completed, she was too weak to travel and died one year after its dedication.

Each window in St. Joseph Chapel is a reflection. The St. Alexius window reminds chapel visitors of both St. Alexius and Mother Alexia, each of whom had a lifelong mission to care for the sick, the poor and all in need.

By Sister Marian Abing

Having grown up in a large family, it was not uncommon for me to see my Mom sit at the kitchen table and breast-feed my baby brothers and sisters. That beautiful sight often comes to mind when I meditate on Mary caring for the baby Jesus. How often Mary must have had to sit down and feed her baby.

Having grown up in a large family, it was not uncommon for me to see my Mom sit at the kitchen table and breast-feed my baby brothers and sisters. That beautiful sight often comes to mind when I meditate on Mary caring for the baby Jesus. How often Mary must have had to sit down and feed her baby.

A mother’s milk is not only the best nourishment for any infant; it also creates a unique bond between them. There is simply no closer bond than the giving and sharing of your own life.

In the St. Joseph Chapel pelican window, we are given the Church’s symbol of a mother sharing her life’s blood with her babies. For Christians in the Middle Ages, the pelican was a familiar and powerful religious symbol of love, self-sacrifice, and charity. St. Thomas Aquinas, a great Doctor of the Church, wrote of this symbol in his hymn, Adoro te devote:

Bring the tender tale true of the pelican;

Bathe me, Jesus Lord, in what Thy bosom ran

Blood whereof a single drop has power to win

All the world forgiveness of this world of sin.

The Chapel window shows a strong, looming mother bird looking down at her young with love and concern. If she cannot give them the regular nourishment of small fish, she will use her beak, gash into her breast, and feed them with her blood.

The baby pelicans open their little beaks as wide as they can because they are very hungry. The droplets of blood come directly from the mother to the little mouths and satisfy these little ones. The warm, nourishing blood soothes them, calms them, and probably quiets them to go to sleep.

In similar ways, when we are nourished in the Eucharist with Jesus’ Body and Blood, we are strengthened and calmed down. We feel especially close to Jesus in that moment. How fortunate we are that we can receive this nourishment daily at Mass! We are fed with the precious Blood of Jesus, knowing and believing that even one single drop of Jesus’ Blood can wash us clean.

The touching legend of the pelican encourages us to meditate and ponder the love story of Jesus’ suffering and death on the cross. He said yes, offering his life’s’ blood from the many gashes in his body, from the whip, the thorns, and ultimately, from the crucifixion itself. Jesus’ willingness to give his life will always tell us of his great love and concern for us, and for our spiritual survival.

Since we live in Christ and are the Body of Christ in the world today, we too must be willing to give our lives, to share our blood, to show the love and charity of Jesus in our world. We must strive daily to follow Jesus and “bring the tender tale true of the pelican” in our humble lives.

By Maureen Hellwig, Associate

Through the ages, the image of a dove holding an olive branch has appeared in many cultures and is always associated with love and peace. It appears in Aztec, Greek, and Hindu imagery, and, in our Judeo-Christian tradition, in the story of Noah’s ark. Early Christians used the dove image when they portrayed the sacrament of baptism. They knew well the story of the Baptism of Jesus and the narrative in all four gospels that mentions the appearance of a dove as the embodiment of the Holy Spirit.

Through the ages, the image of a dove holding an olive branch has appeared in many cultures and is always associated with love and peace. It appears in Aztec, Greek, and Hindu imagery, and, in our Judeo-Christian tradition, in the story of Noah’s ark. Early Christians used the dove image when they portrayed the sacrament of baptism. They knew well the story of the Baptism of Jesus and the narrative in all four gospels that mentions the appearance of a dove as the embodiment of the Holy Spirit.

Why the dove? Naturalists tell us that doves mate for life and give great care to their young. They are harmless birds that tend to nest close to human settlements, so they have been seen by many peoples, everywhere, for thousands of years. What better symbol, then, for the omnipresent Holy Spirit, God’s love in us and all around us in the universe? It was the sign of God’s blessing at Jesus’ Baptism, and the promise that even when Jesus no longer physically walked among us, the Father was sending the Holy Spirit to be with us always.

No doubt, Mother Alexia would make sure that such a symbol of God’s love would be a theme of one of the windows in St. Joseph Chapel. She, and every Franciscan, knows the prayer of the saint from Assisi that begins, “Lord, make me an instrument of your peace.” As these windows were being manufactured in Europe and then shipped to the United States during World War I, the dove of peace was protecting this special cargo. The dove’s presence in chapel continues to remind us today that war—or violence against humanity in any form—is never a solution.

Let us consider an excerpt from a prayer by Joyce Rupp in her book May I Have this Dance?:

Come, Spirit who is our Light.

Shine among the shadows within.

Warm and transform our hearts.

Come, Spirit Comforter and Consoler.

Heal the wounded. Soothe the anxious.

Be consolation for all who grieve and ache.

Come, Spirit, strength of wounded ones.

Be warmth in hearts of those grown cold.

Empower the powerless. Rekindle the weary.

Come, Spirit, source of our peace.

Deepen in us the action of peacemakers.

Heal the divisions that ravage the earth.

By Sister Ruth Hoerig

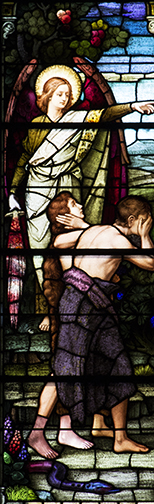

The fall of Adam and Eve from the Book of Genesis is one of the most powerfully portrayed stories displayed in the stained-glass windows of St. Joseph Chapel. Located in the front upper balcony on the Gospel side, we see St. Michael dramatically driving Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden with a flaming sword. The faces of Adam and Eve reveal disturbing, agonizing distress and their lowly, bent posture conveys the fear and dread they are experiencing as they exit the garden. We reflect in wonderment about the meaning of this mysterious and enduring story of our faith.

The fall of Adam and Eve from the Book of Genesis is one of the most powerfully portrayed stories displayed in the stained-glass windows of St. Joseph Chapel. Located in the front upper balcony on the Gospel side, we see St. Michael dramatically driving Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden with a flaming sword. The faces of Adam and Eve reveal disturbing, agonizing distress and their lowly, bent posture conveys the fear and dread they are experiencing as they exit the garden. We reflect in wonderment about the meaning of this mysterious and enduring story of our faith.

For the past five centuries, the Church has taught that the stories in the Bible really happened just as they are described. Our faith clearly taught the awful truth of the fall and the mystery of sin portrayed in this stained-glass window. But author and teacher Father Richard Rohr tells us that a literal interpretation of the Bible may hold the least important meaning for the soul. Good religion, art, poetry and myth point to the deeper levels of truth that factual or literal knowledge can’t fully explain. Guided by biblical scholars, therefore, we seek to unveil the deeper questions of human life, truths about human reason, freedom, pride, suffering and the relationship between God and humanity revealed in the Book of Genesis.

The creation story originates from an overflowing abundance of love, joy and creativity. Genesis 3 tells us Adam and Eve “walked with God in the cool of the evening.” This is the original blessing that they enjoy: resting in His presence. God’s original plan for Adam and Eve is for them to flourish in the garden of paradise laden with delightful things. The lush vegetation and magnificent trees represent all the things that make life wonderful. This is paradise. This is heaven.

Though they have everything they need, God asks them to trust him by not eating the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. The story goes on to say that Adam and Eve eventually get the idea that they can become like God if they eat the forbidden fruit, so they decide to claim for themselves the prerogative of determining good and evil. By losing their trust in God—choosing personal power over reliance on God—they lose the power they had. They give up their ability to draw strength from union with God. This is the original sinfulness of the human race.

The story implies that there are some innate capacities in the human soul that threaten to upset the tranquility of our life with God. Everything depends on whether we recognize our place in the universe as creatures of God, acknowledging God as our Creator.

We begin with grace—with creation. When we live in right relationship with God and others, we are at peace with ourselves and the world. The garden reflects this perfect harmony. God alone is God and we are his creatures. But when we try to rely on our own limited enlightenment without the help of God, we lose our way. Only God’s way leads to salvation.

Father Rohr reminds us that the biblical tradition teaches that first we must see God clearly. In other words, we must first encounter and experience God’s original blessing (as opposed to original sin). Only by discovering and participating in God’s original plan for us can we find our way to self-surrender; that is, to become open to God’s love for us and God’s will for us.

In other words, our life is not about us; we are not the center of the universe. Rather, we are part of God’s great design. To believe this in our bones and to act accordingly is to have faith. When we operate out of this transformed vision, amazing things can happen, for we have surrendered to “a power already at work in us that can do infinitely more than we can ask or imagine.” (Ephesians 3:20)

Sources:

-

Richard Rohr, OFM, Great Themes of Scripture and the Center for Action and Contemplation website.

-

Bishop Robert Barron: Word on Fire homilies

By Sister Margaret Sue Broker

I call this window “The Window of Many Names.” The parable portrayed is most often called the parable of the Prodigal Son, but it has also been referred to as the parable of the forgiving father, or the loving father. All these titles contain a truth about prodigality, forgiveness, and love. Perhaps the name we use is based in part on where our own heart feels most at home at a given point in our life.

I call this window “The Window of Many Names.” The parable portrayed is most often called the parable of the Prodigal Son, but it has also been referred to as the parable of the forgiving father, or the loving father. All these titles contain a truth about prodigality, forgiveness, and love. Perhaps the name we use is based in part on where our own heart feels most at home at a given point in our life.

Growing up, I heard the parable referred to only as the story of the Prodigal Son, who squandered his father’s money living a sinful life. He came to his senses, returned home and was forgiven. Later, as I took on the work of preparing children for the Sacrament of Reconciliation, my heart and mind moved toward a father who could forgive because of his unfettered, unconditional love.

Father Pierre de Chardin said something to the effect that we are not human beings in search of a spiritual experience, but rather, we are spiritual beings immersed in human experiences. This window certainly illustrates the human experience of a father’s love. As members of a living group, a work group, or a community, there are times when we find ourselves immersed in the human experience of needing forgiveness and love.

Look behind the son and his father and notice that there is the mother adding her bit. I like to think that she is encouraging both the father and the son. She is giving her blessing to what is occurring. She quietly lets everyone know that all is well at the moment.

Again, I believe that frequently in life, we are called to be the one who quietly upholds and encourages others when they feel the world is against them. We can’t solve their problems, but we can listen. We can be there for them. And we can let them know that we are not judging them, but rather we are accepting them where they are at that moment.

By Sister Maureen Jerkowski

After Jesus had finished speaking, he said to Simon, “Put out into deep water and lower your nets for a catch” (Luke 5:4)

Jesus was standing by the shore of Lake Gennesaret. The large crowds were pressing in on him to hear the word of God, so Jesus borrowed one of two boats near the shore. The Gospel writer tells us, “He got into the boat, the one belonging to Simon” and “remaining seated, he continued to teach the crowds from the boat.” Sitting was the usual teaching position.

Jesus was standing by the shore of Lake Gennesaret. The large crowds were pressing in on him to hear the word of God, so Jesus borrowed one of two boats near the shore. The Gospel writer tells us, “He got into the boat, the one belonging to Simon” and “remaining seated, he continued to teach the crowds from the boat.” Sitting was the usual teaching position.

The boat, in the Gospel, is frequently a symbol of the church community and a symbol of what is to come in the near future. Jesus tells Simon to go out into deep water and start fishing. “Master, we have been hard at it all night long and have caught nothing; but if you say so, I will lower the nets.”

The nets were hardly in the water when they were filled with fish. Simon, who was arrogant and all knowing, is totally overcome. He knew there were no fish, so this man is someone special. “Go away from me, Lord, I am a sinful man!” Simon’s reaction is that of a person in awe of the presence of God’s overwhelming power and goodness.

Jesus reassures Simon and his companions, “Do not be afraid.” He is calling them to the work of building his Kingdom, a sign of a much greater “catch” of people to be made by the new community.

Simon and his companions depended on their boats and nets for their livelihoods. Their families’ security was at stake. But they left everything. This is faith. This is trust.

Perhaps the most important thing we need to learn is that it is safe to trust. As an international congregation, we trust Mother Alexia’s words that “The needs of the times are the will of God for us.”

One current need of our times is to address the refugee crisis. People of faith are displaced due to conflict, climate change, natural disasters, persecution, violence, poverty and inhumane living conditions. They literally leave everything behind as they search for a better life, trusting that God will provide.

Pope Francis advocates a shared response to this crisis by the political community, civil society and the church. He said that response efforts could be described with four verbs: welcome, protect, promote, and integrate.

Today, our community is responding by offering a home in Milwaukee to two newly arrived families fleeing persecution. In ministry at Maryville, Illinois, sisters provide shelter to unaccompanied refugee children. These children trust that God will take care of them on their journey, and they risk everything for a better life. They leave behind their homeland and their parents. They are far from loved ones, and arrive with nothing but the clothes on their backs. They are vulnerable and need our protection.

As people of faith, we are continually asked to let go, and to trust that it is safe to let ourselves put out into the deep waters and fall into stronger and safer hands than our own. God will provide.

By Sister Madelyn Gould

How fortunate are we to have Jesus and the children right in our midst. We only need to walk down the long terrazzo corridor leading to our magnificent St. Joseph Chapel. Before entering the large wooden door leading to its vestibule, pause to remember who we are as a religious community.

How fortunate are we to have Jesus and the children right in our midst. We only need to walk down the long terrazzo corridor leading to our magnificent St. Joseph Chapel. Before entering the large wooden door leading to its vestibule, pause to remember who we are as a religious community.

Once inside the vestibule, look left to be inspired by four beautifully detailed stained glass windows depicting the ministries of the School Sisters of St. Francis. The second panel from the entrance illustrates Jesus warmly welcoming the little children. The scripture passage Mark 10:13-16 comes to mind. “And they were bringing children to {Jesus} that he might touch them, and the disciples rebuked them. But when Jesus saw this he became indignant and said to them, ‘Let the children come to me; do not hinder them, for to such belongs the kingdom of God.”

“Let the children come to me,” Jesus insists. His message has echoed through the years in the hearts and lives of the School Sisters of St. Francis. Three young women, destined to become the foundresses of the School Sisters, heard Jesus’ message when they joined a small religious community in Schwarzach, Germany. The group gathered to care for orphans, a common practice in the mid-19th century with its many social needs. Emma Francisca Höll (Sister Alexia), Paulina Schmid (Sister Alfons), and Helene Seiter (Sister Clara) were among those who followed Jesus’ injunction to let the children come to them. They radiated Jesus’ care and compassion to these youth.

Because of the political unrest in the 1860s, Sisters Alexia, Alfons and Clara chose to follow the many Germans immigrating to America. Great was the need for teachers of those children. The three Sisters found a home in New Cassel, Wisconsin, now part of the Village of Campbellsport. Within 21 days of their arrival, two orphans were dropped at the Sisters’ doorstep to be educated. Once again, the gospel passage of “Let the children come to me” echoed in the hearts and lives of those sisters.

From this small beginning sprang many schools in diverse places and on several continents. “Let the children come to me” is a scriptural passage that has provided focus to the ministry of the School Sisters of St. Francis from its very beginning until the present.

While educating youth is undeniably a significant way of leading children to Jesus, we are invited to expand our notion of “children” to include all who are like children in their trust and dependency on God. To these, too, Jesus says, “Come.” He wishes to fill all childlike individuals—you and me—with His peace, His compassion, His vision for our world.

Spend some quality time gazing at that window. Envision yourself in the face of one of the little ones nestled close to Jesus. Let the Holy One enfold you in his arms. Recall the individual School Sisters who have touched your life through their ministry of education, by their gifted ways of enfleshing the familiar gospel passage, “Let the children come to me.”

Pause again upon exiting our chapel to remember how you, too, have lived this gospel message. Consider how many children we as devoted sisters have been blessed to serve throughout the nearly 150 years that our religious community has thrived. Add to that inestimable number all the adults influenced by our roles. Give praise and thanks for the continuing ministry of education embraced by the School Sisters of St. Francis from the welcoming of those first two orphans in Wisconsin.

By Sister Fran Hicks

Journeying down the aisles of our St. Joseph Chapel, reflecting on the magnificent stained glass windows whose vibrant colors draw us into the stories they tell, we are especially touched by the flight into Egypt.

Journeying down the aisles of our St. Joseph Chapel, reflecting on the magnificent stained glass windows whose vibrant colors draw us into the stories they tell, we are especially touched by the flight into Egypt.

We see Jesus, Mary and Joseph fleeing under the cover of darkness to escape the murderous violence of King Herod. Joseph is watching, vigilant, cautious, trusting in God’s protection of his family, while still having the emotions of fear and uncertainty.

Mary is courageously clutching her son close in her sheltering arms, praying that all will be well as they go over the rocky mountain roads and into a dangerous and unknown desert. But they are not alone. Angels have been a constant presence in Joseph and Mary’s story from the beginning, and there is a guiding angel at their side in this flight.

The Holy Family now becomes a migrant family facing the same questions as the 63 million migrants and refugees on the move around the world today: Will our supplies last? Will we be robbed of the little we have? Will we be imprisoned? Will we be welcomed and survive in a foreign land?

In the days before global mass media, we could only imagine the suffering of these people. Now, from every form of media, we have the vivid images of their desperation, rejection, separation and even death as they risk everything. They’re not even looking for a better way of life, just for life itself.

What is our response? Do we act on the scripture passage from Leviticus 9:33-34? Do we welcome the stranger? Do we live the gospel passage from Matt: 25: 35-40: “…I was hungry and you gave me to eat; thirsty and you gave me something to drink …”?

Looking at the stained-glass window of the Holy Family in flight, do we not see the faces of the migrants of today? Pope Francis calls to us when speaking about migrants: “Brothers and sisters don’t be afraid of sharing the journey. Don’t be afraid of sharing hope.”

By Sisters Bernadette Luecker and Mary Jane Wagner

This we know: St. Cecilia was born in Rome during the second century and died in the third century. She died as a martyr and we are not certain if it was in Rome or in Sicily. Tradition marks her feast day on November 22, a date that is precious to church musicians and perhaps beyond, to include all musicians. Cecilia is among seven women named in the Canon of the Mass (Eucharistic Prayer I).

This we know: St. Cecilia was born in Rome during the second century and died in the third century. She died as a martyr and we are not certain if it was in Rome or in Sicily. Tradition marks her feast day on November 22, a date that is precious to church musicians and perhaps beyond, to include all musicians. Cecilia is among seven women named in the Canon of the Mass (Eucharistic Prayer I).

Legend tells us that Cecilia was a young Christian of high rank. She was given in marriage by her parents, to a noble pagan youth named Valerianus (Valerian, Valerius). When, after the celebration of the marriage, the couple had retired to the wedding chamber, Cecilia told Valerianus that she was betrothed to an angel who jealously guarded her body; therefore Valerianus must take care not to violate her virginity. Valerianus wished to see the angel, whereupon Cecilia sent him to the third milestone on the Via Appia where he should meet Bishop (Pope) Urbanus. Valerianus did as he was told and after speaking with Pope Urbanus, was baptized by him. Valerianus returned to Cecilia, a Christian. An angel then appeared to the two and crowned them with roses and lilies. Tradition has it that both Valerianus and his brother were martyred.

Legend says that Cecilia, before being taken prisoner, arranged that her house should be preserved as a place of worship for the Roman Church. After a glorious profession of faith, she was condemned to be suffocated in the bath of her own house. She remained unhurt in the overheated room, so then was to be decapitated. When the executioner let his sword fall three times without separating her head from the trunk of her body, he fled. She lived three more days; she made dispositions in favor of the poor and provided that after her death, her house should be dedicated as a church. Pope Urbanus buried her among the bishops and the confessors in the Catacomb of Callistus.

How is St. Cecilia portrayed in this window? Cecilia and her husband Valerianus are each receiving a crown of laurels from an angel. They appear to be entering heaven; Cecilia is shown with a halo. Above them, we see three angels, one playing an early string instrument like a violin or viola; another angel playing an early guitar. Organ pipes are in the background. Other figures in the window are a group of three women, in various postures of prayer, looking towards Cecilia and Valerianus. On the opposite side is a man observing this couple. We are invited to become witnesses of this glorious moment.

Does the angel handing them the crown of laurels (lilies and roses) symbolize their ultimate crown of victory? This appears to be a joyful and celebrative moment, judging from all the people and angels in the window. Cecilia and Valerianus are rejoicing. Could this be their wedding? According to iconography, while musicians played at her nuptials, Cecilia sang in her heart to God.

Is this vision depicting their journey of faith leading to their martyrdom? We know they were martyrs, though this is not evident in the window. The couple seems to be moving forward; perhaps they have both already crossed the threshold of martyrdom.

Since both are martyrs, is this vision of Cecilia and Valerianus a depiction of their receiving the crown of life, welcoming them into eternal life? Cecilia has a halo which is a sign of holiness in the life to come.

Further thoughts

Cecilia is one of only seven women mentioned in the first Eucharistic Prayer of the Mass. She is among the list of saints (deacons, priests, bishops, popes, married and single laywomen, and virgins) to be worthy of martyrdom. This list of martyrs represents the universal call to holiness.

Tradition tells us that before she died, Cecilia made provisions for the poor and she willed that her house be dedicated as a place of worship. She recognized the connection in Eucharist between prayer/worship and service/social justice. Just as the early Christians sang songs when they gathered, so too, she must have known in her heart and mind, the impact and power of music in sung prayer. Truths and understandings of our faith are often articulated in the texts that we sing: prayers, hymns, psalms and acclamations. Instrumental music contributes to the environment of worship and to a deeper as well as a heightened experience of prayer and of communal worship.

How did her patronage of musicians come to be? We don’t know the answer. We do know that artists reflect the understandings of their culture. In most icons of Cecilia, as well as in paintings throughout the centuries, she is depicted as playing either a viola or a portative organ. In this window, the angels are playing the instruments and she is shown with her husband. None of these instruments even existed in the second--third century. It is fair to say that the legends about her evolved, impacting the art that depicts her.

It is good to ponder the various stories evoked in this window. These ponderings can lead one to a deeper level of faith and inspiration, of support and patronage. We rejoice with Cecilia for her legacy to make her home a place of worship. Associated with both singing and playing, she is iconic for all musicians. Soli Deo Gloria!

By Sister Joan Puls

St. Francis of Assisi very deliberately chose to walk in the footsteps of Christ. From the beginning of his conversion, he had a great devotion and veneration for Christ crucified.

St. Francis of Assisi very deliberately chose to walk in the footsteps of Christ. From the beginning of his conversion, he had a great devotion and veneration for Christ crucified.

One morning in 1224, two years before his death, Francis was absorbed in prayer on a slope of Mount Alverna when a seraph with six wings appeared to him. When the vision disappeared, the wounds of Jesus were imprinted on Francis’ body. Until his death, Francis tried to conceal the wounds to the best of his ability. However, his brothers knew about them, and reliable witnesses attested to this extraordinary event.

The feast of the Stigmata of St. Francis is celebrated on September 17. Franciscans celebrate this as a recognition that what appeared externally on Francis’ body reflected his inner conformity to the lived example of Jesus. The imprinting of the same wounds that Jesus suffered in his crucifixion was consistent with Francis’ compassion for the suffering Christ, and for the suffering of all creatures, the lepers, the poor, and the sick.

We are called to be in solidarity with the suffering body of Christ in our world today: the marginalized, those trafficked and enslaved, the abused, and the lepers of our time.

Francis lived and embodied the person of Christ, breaking down barriers, seeing all people, all creatures, as brothers and sisters. He was drenched in his love for the Christ whose features he found in the least and the lowliest. The theologian Hugh of St. Victor wrote, “Such is the power of love that it transforms the lover into the beloved.” How true this was for Francis in his identification with the sufferings of Christ!

We make Christ visible in our world by bearing the marks of Christ in our thoughts, words and deeds. When we choose to follow in the footsteps of Christ, who knows where it will lead?

Our world today bears a crucified face. Only love can begin the transformation of the sufferings of those among us, our brothers and sisters. Do we have at the core of our lives this desire to feel and to share the suffering love that God has for the world, that Jesus poured out with such generosity, and that visibly marked St. Francis?

By Sister Irene Zimmerman

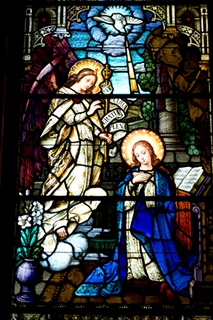

In St. Joseph Chapel, halfway up the nave, is a large and glowing stained glass window depicting the Annunciation. Let’s walk there together.

In St. Joseph Chapel, halfway up the nave, is a large and glowing stained glass window depicting the Annunciation. Let’s walk there together.

The beauty of this window is indeed breath taking, especially when bright noontime sunlight shines through it. Was its placement on the south side deliberate? We can only guess this to be so. But we do know that the real event of Annunciation didn’t look anything like this. Mary didn’t own such beautiful clothing. She lived in “the boonies” of Galilee. It’s likely that she was already adept at spinning wool from the local sheep and weaving it into her own clothes – a skill she demonstrated to perfection later by creating a seamless robe for her grown son, Jesus.

No, young Mary was not born into riches and did not dress like this. But for Mother Alfons, “Nothing is too beautiful for God,” and that would have included God’s mother. How our foundress must have loved to picture this courageous young woman, so transparent with grace, in beautiful stained glass created by the artists of Innsbruck. It was brought over safely through the dangerous, U-boat infested Atlantic waters of 1914.

Think about what is depicted here. Mary was alone with God’s messenger. This magnificent, frightening angelic being was greeting her as “full of grace” and asking her to give human life to God’s son. Luke tells us that she was afraid. Did she long to run to her mother to say, “Hide me, Mother. I’m only a child. I want to stay home with you and Abba a while longer. I’m afraid!”

The colors seem to shimmer and shake as we realize that she could have said “No.” God wasn’t forcing her. Even though it was now “the fullness of time when all was in readiness,” she could have refused; and then the Holy Spirit might have had to wait another thousand years or more to create another woman so full of grace. No one in the centuries to come would accuse Mary of delaying God’s great break-in into the universe. We would never even hear of Mary, Mother of God!

What unimaginable leap into maturity was being required of her in this moment! One small syllable of consent and God would begin to grow inside her. God would enter the universe and become a part of it forever!

But wait. Mary was no naïve little girl. Nor was she too scared to ask her necessary question before she gave her consent: “How is this to be done, since I am a virgin?”

O beautiful, strong, courageous woman! Thank you for your wholeness, your holiness, your loud, momentous “Yes” to God, your Creator and ours. Because of you, the universe is forever pregnant with divine life, growing in each of us. The whole universe is on its way to Bethlehem. Help us, like you, to discern and ask our valid questions, and then to say “Yes” to what God asks of us individually, as a congregation, and as Church as we move into the unknown future.

How Can This Be, Since I Am a Virgin?

(Luke 1:34)

Your world hung in the balance of her yes or no.

Yet, “She must feel absolutely free,” You said,

and chose with gentle sensitivity not to go

Yourself—to send a messenger instead.

I like to think You listened in at that interview

with smiling admiration and surprise

to that humble child who—

though she didn't amount to much in Jewish eyes,

being merely virgin, not yet come to bloom—

in the presence of that other-worldly Power

crowding down the walls and ceiling of her room,

did not faint or cry or cower

and could not be coerced to enflesh Your covenant,

but asked her valid question first

before she gave her full and free consent.

I like to think You stood

to long applaud such womanhood.

© Irene Zimmerman

By Sister Deborah Fumagalli

“What you hold, may you always hold. What you do, may you always do and never abandon…the Spirit of God has called you.” (Blessing of St. Clare)

“What you hold, may you always hold. What you do, may you always do and never abandon…the Spirit of God has called you.” (Blessing of St. Clare)

On the south wall of the Adoration Chapel, the stained glass window of Clare illuminates the space with the brilliance of multicolored light that emanates through the darkness. True to her name, “Chiara,” meaning light in Italian, enlightens both her world and ours with the witness of her life that transcends time.

The 13th century in the region of Assisi was wrought with much social and political tension. There were great divides: the economic disparity between unimaginable wealth and extreme poverty, and the violence of the Crusades and other wars contrasted with the gallantry and courage of chivalry.

Clare Offreduccio (1193-1253) came from a privileged family of nobility and was prepared for a life of generosity and service. As a young woman she frequently heard the preaching of Francis Bernardone (1181–1226), and Clare was moved by his love for the Gospel message. So inspired, she rejected her family’s status and plan for her life and founded her own community, the “Poor Ladies,” becoming the first woman to formulate a rule for religious women. Clare generated a spirit of unity among her sisters through a common commitment to the Gospel.

Why was Clare so determined to live a life of poverty?

“Clare, like Francis, did not choose poverty for philosophical reasons, nor for practical ones, as a choice making her life more productive or efficient. And neither of them speak about this poverty as a response to the affluence of Church or society in their day, though it was undoubtedly seen by others in that way. The focus of their attention was God’s overwhelming generosity and love, expressed in the free choice of the Son to embrace poverty in becoming a creature. The two disciples from Assisi embraced poverty because it was embraced by their Beloved.” (William J. Short, OFM, Poverty and Joy: The Franciscan Tradition)

Today we acknowledge Clare as the co-founder of the Franciscan movement and Francis’ most faithful follower. Her life embodies devotion to God, kindness, strength, and love for the women who were cloistered with her in the church of San Damiano. She offers us a clear example of how women could fashion their path to a Divine calling. An exemplary servant leader, Clare took unprecedented steps for a woman of her time, maintaining her vision of poverty so that nothing distracted the “Poor Ladies” on their journey to glorify God.

“Go forth in peace, for you have followed the good road. Go forth without fear, for He who created you has made you holy, has always protected you, and loves you as a mother. Blessed be you, my God, for having created me.” (St. Clare)

By Sister Durstyne Farnan, OP

We are greeted in the entrance to the vestibule of St. Joseph Chapel by a large, tall stained glass window of Mary Magdalene at the foot of Jesus anointing him with spices and oil.

We are greeted in the entrance to the vestibule of St. Joseph Chapel by a large, tall stained glass window of Mary Magdalene at the foot of Jesus anointing him with spices and oil.

This window being placed in such an obvious space reminds us that Mary of Magdala has a prominent position in scripture. Mary Magdalene is mentioned 12 times in the gospels, and from these references of her we can see clearly that she is a woman leader. In eight different chapters she is depicted taking a center place among the women. In five other passages she is mentioned. She is alone but always linked to the death and Resurrection of Christ (Mark 16:9; John 20:1, 11, 16, 18). She is the second most mentioned woman, after the Virgin Mary, in the New Testament.

Mary Magdalene has been called the “apostle to the apostles.” With this title she takes her rightful place in history as a beloved disciple of Jesus and a renowned early church leader. Mary is commissioned by Jesus to go and tell the disciples that He is Risen and that now they too share His relationship with the Father. This commissioning discloses to us how much trust Jesus had in Mary’s active fidelity.

Although a woman’s testimony at that time was considered invalid, all four gospel writers make women the primary witnesses to the most important event of Christianity. Mary Magdalene appears in every one of the four gospels. She, along with other women in three of the gospels, goes first, before anyone else, in the early morning to bring spices to reverence the body of Jesus at the time of His death. She is depicted in this window anointing the feet of Jesus with her spices, a most personal moment between Jesus and Mary Magdalene. Her leadership (Mark 16:10; John 20:18), patience (Matt.27:61) and devotion (John 20:16-17) make her a model to emulate.

We now know from scholars that women were leaders in the early Jesus movement. Not only do several biblical passages describe them, but apocryphal, non-canonical writings also reveal women as apostles, deacons, and co-workers, and provide important historical evidence about the church of the first centuries.

In this Jubilee year of St. Joseph Chapel we remember that as Mary of Magdala proclaimed “Jesus is Risen,” so too, the School Sisters of St. Francis have been commissioned by their call to “Come Follow Jesus” and their profession, to preach God’s word through education, health care, pastoral ministry, social service, advocacy work, and the arts.

Let us continue to witness to the Risen Lord and preach the gospel in deed and word.

By Sister Michele Doyle

Many “unknowns” surround the life of Julian of Norwich. The dates of her birth and death are uncertain (c. 1342- 1416), but she lived during turbulent years for the Church torn by schism. Plagues were rampant in the 14th century and she saw nearly half of Norwich die from the bubonic plague. It’s unknown whether Julian remained unmarried or was a widow, and unclear if she was a nun or a laywoman. Even her name is unknown: She became known as Julian because she lived in a cell built onto St. Julian of Norwich Church in Norwich, England. She spent many years of her life secluded from society.

Many “unknowns” surround the life of Julian of Norwich. The dates of her birth and death are uncertain (c. 1342- 1416), but she lived during turbulent years for the Church torn by schism. Plagues were rampant in the 14th century and she saw nearly half of Norwich die from the bubonic plague. It’s unknown whether Julian remained unmarried or was a widow, and unclear if she was a nun or a laywoman. Even her name is unknown: She became known as Julian because she lived in a cell built onto St. Julian of Norwich Church in Norwich, England. She spent many years of her life secluded from society.

What we do know about her comes from her writing. When she was about 30 years old, she was struck with a devastating illness from which she nearly died. After the priest had shown her Jesus Crucified, not only did Julian rapidly recover her health, but she received 16 revelations. For the next 20 years she reflected on these visions, recording her insights in a book called Showings, or The Revelations of Divine Love. It’s believed to be the earliest English-language book written by a woman. It was published by a printer in the early 1500s, long after she had died. The manuscript was discovered about 100 years ago.

Because of Julian’s deep love of the Eucharist, her image was included among other saints whose images surround the Altar of Adoration in St. Joseph Convent’s Adoration Chapel.

In Section Three of the Showings, she writes, “The compassionate, merciful and tender image of God indicates the face of God that Julian desires for all of us to know and understand”—Jesus. The book contains a message of optimism based on the certainty of being loved and protected by God.

Julian was a mystic. Mysticism is often looked upon as a privileged experience for only the “super holy.” But Ruth Burrows, a Carmelite nun, says that mysticism is not simply the province of the saints. “For what is the mystical life but God coming to do what we cannot do; God touching the depths of our being. . .” Julian, though she describes herself as unlettered, went from being a visionary to a theologian. She believes “all shall be well” because divine providence brings good, even from evil.

Our foundresses, in beginning our congregation in a new place, felt that God helped them to do what “they could not do alone” and “all would be well.” We continue to ask God to be with us to do whatever it is we need to do that we “could not do alone.”

By Sister Joneen Keuler

The window of the Good Shepherd, located centrally on the east wall and main floor of St. Joseph Chapel, is the prominent image one sees when leaving the chapel. It beckons us to come close and walk with him.

The window of the Good Shepherd, located centrally on the east wall and main floor of St. Joseph Chapel, is the prominent image one sees when leaving the chapel. It beckons us to come close and walk with him.

As a child growing up on a dairy farm in eastern Wisconsin, I knew little of sheep and shepherds. Although familiar with Psalm 23 and the Good Shepherd discourse in the Gospel of John that’s read each year after Easter, I had no experience with the vulnerability of sheep and their utter dependence on their shepherd for protection. This stained glass window in our chapel continues to be a rich symbol of the constancy of God’s presence and guidance, just as it was when I began my life as a School Sister of St. Francis.

With a sturdy staff in hand, Jesus stands with a young lamb on his shoulder, and is surrounded by other sheep. The sides of the window appear to form the gate through which he is leading his flock. It is the strength and yet gentleness of this Shepherd that draws us close today, just as it has through the years that School Sisters have stepped out and gone forward on new paths.

We said yes to the educating of Native American and black children in the United States when that didn’t seem like the safe thing to do. We built hospitals and staffed clinics in small rural communities when providing health care and solidarity with the people were greater values than large profits or salaries. In our present ministries world wide, we’ve chosen collaboration with all who share our mission of “giving, healing and defending LIFE.” (Response In Faith: Rule of Life, p. xiii)

Pope Francis asks all of us to go to the margins of God’s people, to not fear to be among those “with the smell of sheep” in order to serve. How fortunate we are to have a Shepherd who nourishes us for those journeys, and welcomes us back into the fold to rest and be refreshed. We continue what was begun, and are open to what is new. That is how transformation happens.

By Sister Kathleen Kluthe

In the Reliquary Chapel of our International Motherhouse at St Joseph Convent, we find this stained glass window of our sun and moon with personal faces as a beautiful depiction of St. Francis’ “Canticle of the Creatures”:

In the Reliquary Chapel of our International Motherhouse at St Joseph Convent, we find this stained glass window of our sun and moon with personal faces as a beautiful depiction of St. Francis’ “Canticle of the Creatures”:

“Most High, all-powerful, all good Lord! All praise is yours, all glory, all honor and all blessing. To you alone, Most High, do they belong. All praise be yours, my Lord, through all that you have made, and first my Lord, Brother Sun, who brings the day, and light you give to us through him. How beautiful is he, how radiant in all his splendor! Of you, Most High, he bears the likeness. All praise be yours, my Lord, through Sister Moon and Stars; in the heavens you have made them, bright and precious and fair. Praise and bless my Lord and give him thanks, and serve him with great humility.”

The sun, moon, and all of Creation are one with God. Everything and everyone is connected and interdependent. This cosmic connection in St. Francis’ Canticle, and pictured in this window, challenges us to expand our awareness and deepen our commitment to be one in mind and spirit in the midst of diversity. We recognize our personal connections to one another across cultures, races, religions and geographic boundaries.

It also brings to mind the School Sisters of St. Francis’ Congregational Direction for 2014-2018: “We commit ourselves to spiritual transformation to become more deeply united and more intercultural in our congregation and in our mission.” This is our theme for reflection across all five of our worldwide provinces. Intercultural living is a challenge that requires compromise, dialog and a common and clear vision.

In the spirit of St. Francis and our foundresses, Mothers Alexia, Alfons and Clara, we continue to embrace and welcome the stranger and the marginalized. For Francis, they were the lepers of his society. For our foundresses, they were the many immigrants and refugees. For us, the “outsiders” are the Dalits in India, the Christians in Arab countries, the racial minorities in the United States, the indigenous in Latin America, and the Muslims and many refugees in so many places throughout the world.

Principle One of our congregation’s Response in Faith Rule of Life is “We share Christ’s mission in the world.” The symbol for this principle is fire, which embodies light and energy from the sun and moon. Our challenge is to cast fire—the fire of energy, compassion, warmth, purification and light—into our world.

Fire, light, and energy fuel action, change, and transformation. We have a “burning desire” to work for mutuality, personal growth, and the practice of justice and peace. Let us invite one another to walk into the future with the determination, faith, light, and energy of Saints Francis and Clare, our foundresses, and the many sisters who have led the way over these many years.

By Donna O'Loughlin

In St. Joseph Chapel, we find stained glass representations of stories we’ve read in the Bible as well as much-beloved saints. In this window of the Holy Family, Joseph takes the supporting role, as he so often does in Scripture and art.

In St. Joseph Chapel, we find stained glass representations of stories we’ve read in the Bible as well as much-beloved saints. In this window of the Holy Family, Joseph takes the supporting role, as he so often does in Scripture and art.

Joseph’s gaze and the gesture of shading Mary and baby Jesus from the elements are both practical and metaphorical. A humble carpenter with a young family to raise, he was their protector. After God commanded him in a dream not to forsake Mary, Joseph obeyed and took up the ultimate evangelical torch: He became the adoptive parent of God’s Son and thereby ensured the fulfillment of the Great Promise.

St. Joseph Chapel was named to honor Joseph, the protector of virgins and children. Even before our foundresses crossed the Atlantic, Mother Alexia’s devotion to St. Joseph was resolute. She called him her intercessor when she begged door to door in behalf of an orphanage in Germany. He was the saint who directed our foundresses’ sights to Wisconsin. Due to her confidence that St. Joseph would make things right, Mother Alexia courageously signed a contract for the construction of a new women’s academy in New Cassel in 1874, though she herself had only seven cents in her pocket. In good humor, it has been reported that she named the convent after St. Joseph “to honor him, but also to remind him graciously that it was not yet completed nor completely paid for.” Finally, in 1914, Mother’s devotion to St. Joseph emboldened her to establish homes for the physical and spiritual care of university women in Germany without ready funds.

Both Mother Alexia and St. Joseph lived in uncertain times, albeit 1,800 years apart. With Mothers Alfons and Alexia’s reliance on St. Joseph, St. Joseph Chapel was consecrated in 1917. It has since provided 100 years of formation, blessings, kinship, and more for our sisters. Here, thousands of young women have been received as they dedicated their lives in the service of God and neighbor.

These sisters took up the roles of teachers, nurses, social workers, pastoral care staff, administrators, lawyers, accountants, artists, and musicians. In God’s Holy Name, they continue to pray, advocate for social justice, and provide schools and housing for the marginalized. Their mission to spread the message of love that Joseph’s Holy Family shared with the world 2,000 years ago transcends national boundaries. St. Joseph Chapel is the congregation’s prayer home, inviting all to worship here, enjoy St. Joseph and our sisters’ openness to grace, and engage with the past, present, and future Church.